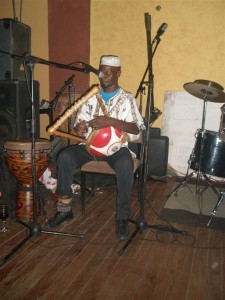

You might remember back in November 2011, while the Singing Wells team discovered the Music of the Luo, they recorded the beautiful sound of the nyatiti, eventually purchasing one for our studio back home! There’s one on the right.

You might remember back in November 2011, while the Singing Wells team discovered the Music of the Luo, they recorded the beautiful sound of the nyatiti, eventually purchasing one for our studio back home! There’s one on the right.

On Day 11 of that field trip in Siaya, Kenya, they saw two nyatiti groups, first The Joginda Boys, featuring Oganda Joginda. Watch and listen:

The second nyatiti group featured Okumu K’Orengo, another fantastic player of the nyatiti. We were reminded of the critical importance of capturing the cultural legacy of East Africa with tribal music when this extraordinary musician, Okumu K’Orengo, died only weeks after our visit. Appropriately, his last recording with us was a funeral song that our team at Ketebul Music felt was the best performance they’d ever heard of it:

The Singing Wells team were also lucky enough to enjoy the sound of one of the best nyatiti players in the world, Ayub Ogada during their field visit in March, where Tabu organised a ‘Hall of fame concert’. He opened the concert with the famous “Kothbiro”, which featured in the film ‘The Constant Gardiner’. Here it is:

There’s a wonderful story about Andy’s recommendation to Gary Barlow’s production team to have Ogada play in a track called ‘Sing’, recorded specially for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. Read more about that here, and give it a listen.

The Nyatiti

Origins: The nyatiti is an african string instrument from Kenya that strongly resembles an egyptian lyre. It is traditionally played by the Luo peoples, an ethnic group now situated in Western Kenya, Eastern Uganda and Northern Tanzania. They were originally from the Nile River Valley and migrated down the River Nile to the Lake Victoria region after the Nubian peoples. In Egypt (particularly around the valley) you can find many instruments that date back over 5000 years, many, like the nyatiti, are also found in Egyptian hieroglyphs (right). The Luo people are related to the Acholi people of Uganda, a tribe we will come across in our next field visit. They play a similar instrument called the Adungu.

Origins: The nyatiti is an african string instrument from Kenya that strongly resembles an egyptian lyre. It is traditionally played by the Luo peoples, an ethnic group now situated in Western Kenya, Eastern Uganda and Northern Tanzania. They were originally from the Nile River Valley and migrated down the River Nile to the Lake Victoria region after the Nubian peoples. In Egypt (particularly around the valley) you can find many instruments that date back over 5000 years, many, like the nyatiti, are also found in Egyptian hieroglyphs (right). The Luo people are related to the Acholi people of Uganda, a tribe we will come across in our next field visit. They play a similar instrument called the Adungu.

Style: As music is mainly functional for the Luo, traditionally a nyatiti player is called upon to play at weddings or funerals, as it can be played as a solo instrument. The intsrument is often performed with a dance, called ‘Goyo Otenga’. Otenga is the Luo word for eagle, and so dancers move their shoulders, arms, fingers, legs and feet like an Eagle.

The Luo often use the nyatiti in ‘Benga music’, a genre of Kenyan popular music. Guitarists from Western Kenya sought to imitate the instrument, and so in Benga, the electric bass guitar is played in a style reminiscent of the nyatiti. This is because the nyatiti has always acted as a ‘bass’, supporting the rhythm during a piece of music. This is demonstrated above in our recordings from November last year. The first major Benga band, Shirati Jazz, happened in the 60s, have a listen:

Benga music is the perfect example of how ancient and traditional music can be kept alive by using the styles and instruments in a contemporary way. One of the keys objectives of the Singing Wells project is to introduce tribal East African music to a new generation of musicians and fans who might not consider it relevant today, through The Influences Series. Some of my favourite prominent Benga musicians of today are Ogwang Lelo Okoth, Musa Juma (below) and Dola Kabarry (below).

Instrument: The nyatiti has 8 strings and is usually played sitting down on a three-legged stool known as the ‘Orindi’, it can be as low as shin level. The player sits with the instrument in front of him whilst wearing a round-iron ring (like a nut) which he taps on the lower bar of the nyatiti to produce a constant beat. On the same leg he wears a ‘Gara’, a bell that shakes along with his foot. Most players wear headgear called ‘Kondo’, which is made of animal skin or feathers, and the dancers would tie ‘Owalo’ on their waist. The body of the instrument is made of a hollowed out fig tree, and then it is covered with cow skin to make the surface of the hemisphere. In the past, female cow’s Achilles tendons were used for strings, but now they are made with fishing lines. The two wooden beams are bamboo sticks and wood chips bonded together using bees wax, which helps create a deep echoing sound.

Instrument: The nyatiti has 8 strings and is usually played sitting down on a three-legged stool known as the ‘Orindi’, it can be as low as shin level. The player sits with the instrument in front of him whilst wearing a round-iron ring (like a nut) which he taps on the lower bar of the nyatiti to produce a constant beat. On the same leg he wears a ‘Gara’, a bell that shakes along with his foot. Most players wear headgear called ‘Kondo’, which is made of animal skin or feathers, and the dancers would tie ‘Owalo’ on their waist. The body of the instrument is made of a hollowed out fig tree, and then it is covered with cow skin to make the surface of the hemisphere. In the past, female cow’s Achilles tendons were used for strings, but now they are made with fishing lines. The two wooden beams are bamboo sticks and wood chips bonded together using bees wax, which helps create a deep echoing sound.

Gender: The nyatiti is traditionally only played by a man. The first four days after a male’s birth and a male’s death in the Luo are said to be very special in their culture. The lower four strings of the nyatiti represent the first four days of his birth, and the upper four strings represent the four days after his death. Anyango, a Japanese woman who now lives in Kenya has become the world’s first female nyatiti player, performing infront of thousands at the 2007 STOP AIDS Concert in Kenya. She speaks native Luo and has become famous for her originality all over Kenya..

The Adungu:

Origins: The bow-harp is

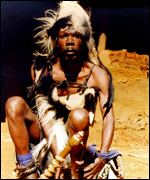

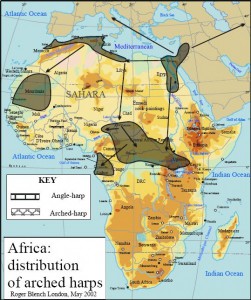

Origins: The bow-harp is  an outstanding example of good Ugandan craftsmanship. Like the Nyatiti, the Adungu came from the traditional bow-harp or ‘lyre’ from the Egyptians. Michael Levy, a specialist in music of the ancient world, was particularly interested in the close likeness between the Ugandan Adungu played today and the Egyptian arched harp, particularly one housed in the British Museum. It’s dated 1534-1296 B.C and was found in the tomb of Thauenany, Western Thebes (right). Some scholars have rejected the theory that African harps and lyres today were originated from the instruments that were created first thousands of years ago, although there is strong evidence to suggest they were, not only due to their likeness, but because of the way the instruments have migrated with their players, as shown on the map (left). Below is a video made by Levy, one of three, describing his theories linking the Adungu with ancient Egypt. Here is his website.

an outstanding example of good Ugandan craftsmanship. Like the Nyatiti, the Adungu came from the traditional bow-harp or ‘lyre’ from the Egyptians. Michael Levy, a specialist in music of the ancient world, was particularly interested in the close likeness between the Ugandan Adungu played today and the Egyptian arched harp, particularly one housed in the British Museum. It’s dated 1534-1296 B.C and was found in the tomb of Thauenany, Western Thebes (right). Some scholars have rejected the theory that African harps and lyres today were originated from the instruments that were created first thousands of years ago, although there is strong evidence to suggest they were, not only due to their likeness, but because of the way the instruments have migrated with their players, as shown on the map (left). Below is a video made by Levy, one of three, describing his theories linking the Adungu with ancient Egypt. Here is his website.

The Instrument: The Adungu is based on the major or pentatonic scale. In modern Africa the Adungu has tuning-pegs, which the Egyptians did not, and play the harp with it away from the player’s body, whilst the Egyptians leant the harp against his chest like a musical hunting bow. Great care was taken to achieve the ideal of sound timbre desired, such as the movable rings attached round the neck of the instrument, one to each string, which are pushed into position just close enough below the string to let it vibrate against the ring. The rings are made of banana fibre sewn into lizard skin. A small wooden wedge was then inserted between the ring and neck to make the fitting of the ring easier and to prevent it from shifting. The position of the rings also played a part in the tunings, along with tuning pegs which the Africans made functional. The harp is constantly evolving, and while in the past tortoise shell was used to make it, it is now largely made out of wood.

The Instrument: The Adungu is based on the major or pentatonic scale. In modern Africa the Adungu has tuning-pegs, which the Egyptians did not, and play the harp with it away from the player’s body, whilst the Egyptians leant the harp against his chest like a musical hunting bow. Great care was taken to achieve the ideal of sound timbre desired, such as the movable rings attached round the neck of the instrument, one to each string, which are pushed into position just close enough below the string to let it vibrate against the ring. The rings are made of banana fibre sewn into lizard skin. A small wooden wedge was then inserted between the ring and neck to make the fitting of the ring easier and to prevent it from shifting. The position of the rings also played a part in the tunings, along with tuning pegs which the Africans made functional. The harp is constantly evolving, and while in the past tortoise shell was used to make it, it is now largely made out of wood.

They come in a variety of different sizes and are often played as an ensemble:

Tradition: Traditionally, the harpist was the only musician ever allowed to play in the room of the royal ladies, whilst there would often have been a harpist situated in the Kabaka’s palace (the chief of the Baganda tribe in Uganda). In some cases, a harpist was blinded by royal command either to make him immune against the charms of his audience or to keep him dependent upon his master. The instrument has a solo character, while it is now often played as an ensemble of instruments (as shown in the videos above), previously a harpist would sit silently during public functions where an ensemble is playing, and then once the orchestra was finished, would strike up and sing his solo, accompanying himself on the harp. The two tallest strings of an Adungu are called ‘minne’ meaning ‘mothers’, the two shortest are known as ‘nyige’ meaning ‘the little ones’, while the centre string (as the bass adungu only has five strings) is referred to as ‘atong’ described as ‘one which receives the voice above’.

Soloist on the Adungu:

Whilst the harp was previously a royalist instrument, like many other styles of music it generally had a ceremonial function, and like the nyatiti the adungu is played at weddings and funerals, such as in the bouncy performance shown in the video below of a Ugandan wedding.

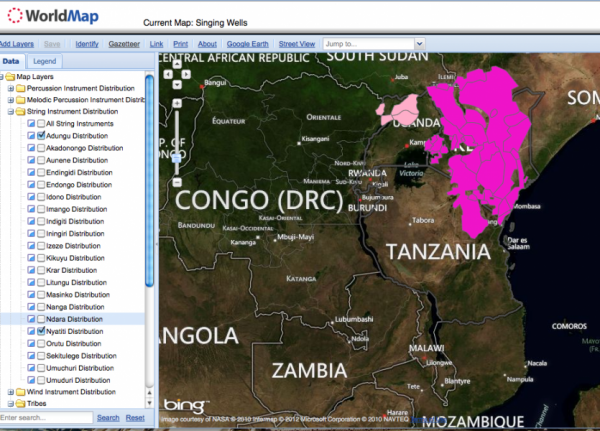

Using our Worldmap we can show a distribution of the Adungu and Nyatiti instruments across Eastern Africa – the Nyatiti is represented in the darker pink, the Adungu in the lighter pink:

References:

‘Saharan Vibe’, (2011), ‘Luo Nyatiti Music from Kenya’, Available: http://saharanvibe.blogspot.co.uk/

Blench, Roger. Reconstructing African Music History: Methods and Results, SAFA Conference, 2002

Ruiz, Ana. The Spirit of Ancient Egypt, Algora Publishing, 2001

‘Anyango Official Website’, 2012 JOWI music, ‘Nyatiti’, Available: http://anyango.com/e/nyatiti/

‘Kaypacha’, Musical Instruments, Crafts, Aboriginal and Ethnic, Available: http://www.kaypacha.com.ar/en/instruments/nyatiti

Wachsmann, K. Trowell, M. (1953). Tribal Crafts of Uganda. 1st. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

‘Traditional Instruments’ of the Uganda People’ (2012), Face Music, Available: http://www.face-music.ch/

‘EgpytSearch Forums’, Wysinger, M. (2008), REAL Ancient Egyptian Music and Dance , Available: http://www.egyptsearch.com