Paul Kelemba (Maddo), Chairman of Ketebul Music, reporting back from the pilot programme…..

When Tabu Osusa and I at Ketebul Music, along with our backers at Ford Foundation, set out to document Kenyan music genres from mid last century and offer them in easy to read, listen and view mediums to today’s audiences, young and old, we were trying to fulfill our dreams of preserving our music heritage for prosterity. We have so far produced two packages and are currently working on three others simultaneously.

Of course the world cannot live in the past and must move on, but there is no future without a past. Countries that have rich music industries and whose music crosses borders have their successes deeply embedded in the music of their ancestors. Southern, Central and Western African nations have their modern music genres deeply rooted in the rhythms, harmonies and melodies of their past resulting in an incredibly strong cultural identity on the world map. Countries that have turned their backs on their roots have a struggling music stage where musicians are caught in a warp trying to experiment with styles that they are clearly not at ease with. I recognize that, as I have mentioned, that things do change. But I would love to see more and more young Kenyan musicians base their work on more acoustic instruments while taking advantage of today’s modern recording equipment rather than being totally reliant on it to produce “robotic” stuff.

There shall exist modern, contemporary music and traditional music. The latter is sometimes viewed as “backward” and is not at the frontline of entertainment in a country such as ours – in fact one must go to great lengths to access it. It’s available on national days in stadia, at “boring” spots such as Bomas of Kenya and at traditional weddings or circumcision fetes deep in rural areas. I’d love to see big name entertainment spots in major towns across Kenya where one can easily be entertained by traditional troupes – who shall be reasonably remunerated for their efforts (and not depend on handouts from politicians who use them to spread their own skewed policies or lack of them in the music industry). It would be with absolute satisfaction to watch these groups outside their tourist hotel runs as occurs with the groups we covered in the pilot phase of the Singing Wells Project at the Kenyan coast.

So, when Abubilla Music appeared on the horizon, there was a sigh of relief from us at Ketebul Music. Just about time! We could just now most likely expose the country’s music roots to larger audiences, in a unique way, different from the grainy footage of government “tourist promotional” documentaries dating from the 1960s.

I was born in Nairobi 48 years ago. At 14, my future music career came to a crashing halt when I was kicked out of the school choir for miming. I wouldn’t dare sing; my voice is just a notch better than a toad’s. My attempt to learn guitar was also thwarted when my finger tips formed that kind of stuff you find on your heels if you don’t wear shoes. I grasped the next best thing: art that I have a passion for, rising to become one of the most read cartoonists in the region. But my enthusiasm for music remains intense. So when I am not drawing caricatures of politicians or throwing barbs at societal misfits, I try to be part of the forces that shall try shape a revamped local music theatre. I hosted jazz sessions in the late 1990s and have occasionally assembled a group to do brief stints at pubs. I also presented an “R&B” show on the national broadcaster, KBC. Most of the time, Tabu Osusa has lurked in the background with brotherly advice.

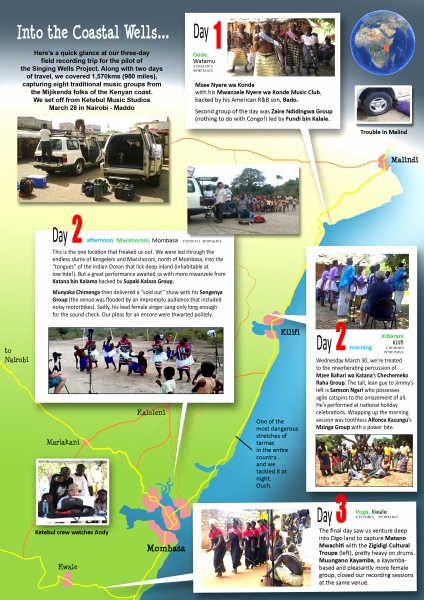

March 26, 2011, about 22.00 hours, JKIA Nairobi. Ketebul had partnered with Abubilla on the Singing Wells Project, just about the best thing, in my view, that has happened to the dwindling fortunes of Kenyan traditional genres of music. Tabu and I were at the airport to receive James Jimmy Allen and Andy Patterson from Abubilla. I’d met Andy towards the end of 2010 on his first visit to Africa and we’d gotten on fine. I was looking forward to meeting Jimmy. Tall, burly American now domiciled in the UK. One look at him and I saw a professional we could do business with. I immediately loved his good nature too. We ferried them to their hotel and let them recover from the shock of encountering a moon directly overhead. The next day, Sunday, they were busy at our studios before we ushered them to Sippers Restaurant where we’d lined up a team of brilliant music performers to welcome them and also accord them the opportunity to check if their hi-tech equipment would work well south of the Equator. Blow by blow accounts of the field recordings starting Tuesday March 29 to Thursday March 31 are available elsewhere at this site, so I will just fling you here and there instead (see graphic below).

For the material-gathering first step on the Singing Wells Project, which shall eventually cover the whole country, the Kenyan Coastal region was selected. The strip is mainly composed of the Mijikenda group of culturally related people; the Chonyi, Rabai, Duruma, Kauma, Kambe, Ribe, Jibana and the more known Giriama and Digo whom we focused on at this stage. Their music is relatively well known at the national level and is highly dependent on percussion with vocal solos and harmonies and pretty is rhythmic. Very sexy. There are various styles including sengenya, chechemeko (actually a dance style) and mwanzele which has been exported to Nairobi and souped up as ‘nzele’. The Mijikenda (literally “the nine clans”) also employ the use of a vast array of impressive instrumentation such as kayambas, marimbas, flutes, horns, various cow-hide drums and shakers. I often point out to the “misuse” of the synthesizer in generation of drums beats and percussion in modern recordings. However, modern technology can greatly enhance these acoustic sources of music if one chooses to start from there. Imagine the sound of the Chechemeko Raha group with that insistent chime of their multi-shakers; it would serve well on a recording with prudent arrangement. It doesn’t take knowledge in ethnomusicology to cherish the end result.

Jimmy and Andy are amazing. The latter’s grasp of African traditional music and how to digitally emblazon the stuff was remarkable considering that this young gentleman from the north of Britain was on his second visit to the African continent. Jimmy is a sheer professional. We irked him earlier on in Nairobi with our team turning up late for introductory sessions. And that’s one of the lessons we learnt; time and its management (everyone knows about it but can’t keep it). The Ketebul Team is now eager to arrive at work stations hours early in the future phases of the actual recording of SWP. The Abubilla Team’s modus operandi rubbed off us in a highly positive way. I observed coordinated responses and easy flow from equipment set up, material capture to equipment disassembly on the part of the Ketebul crew. The local boys were also very cohesive and moved as one by the end of the first day at Gede in Watamu. I can describe this as one of my highlights. The team is set for go and there is no need for any overhaul of its composition except perhaps where some extra personnel may be required in future. The training aspect on this field trip was excellent. I don’t think it was the allure of a couple of cold beers at the end of each day that made the boys bring forth their best.

Another beautiful occurrence at this stage of the project is that the Ketebul team laid its hands on new equipment that they were eager to be exposed to. I’ll take a back seat here (I come from the days of Cool Edit and I’m still firmly embedded there). The boys were thrilled by the simple yet effective outdoor recording suite, the software – Pro Tools 9 – the Mac Book and all that sound capture gadgetry (listed elsewhere). On our first day of recording, Bado – son and back up vocalist for his father’s Mwanzele Nyerere wa Konde Music Club – was mesmerized by the equipment’s clear sound picking in an outdoor environment. The equipment is now tried and tested and we’re geared up to plunge into the subsequent phases of the larger project.

SW Coast Map

Maddo’s Take on the Trip

Steve was at his very best, Willy was as industrious as his size would allow, Pato was the always cool and calculating professional on an outing, Jesse grasped the audios with gusto under Andy’s watchful eye while Tabu barked orders and I made sure we were at the right place on the GPS (the latter two had also special duties of Executive Drivers). Winyo made sure that we came back with a bridge between his melodious voice and the harmonies of the Giriama and Digo.

Back to Jimmy. We discussed a few things further afield and it is nice to know that an individual such as he with a financial consultancy background can also possess so much love for art. Most of the folks here with such backgrounds stick to buying a fleet of matatus (communal taxis), to running pubs playing Congolese music and poorly rendered local American hip hop and rap to importing cement. Jimmy is outgoing too. He can enjoy his cold beer (while updating his blogs and talking to you at the same time). It seemed that he was working every moment of his life. The only thing that scared him was the hotel room in Malindi. We’d booked the place for its beautiful name but promptly found out that we’d walked into a… (deleted!). Old, retired Italians prowled the place with semi retired local call girls in tow – the kind with skin falling off their faces after decades of chemical assault by skin lighteners.

On our second morning at the hotel (and weren’t we glad we were leaving), this lady passed by our table, which I was manning as the others loaded the trucks, and asked of me what “TV station” we were. I wanted to inform her we were from You-Got-Caught TV but instead volunteered the nature of our mission. She seemed relieved, skipping over to her ageing boyfriend to convey the “good news” – that we weren’t spying on them – in splattering Italian. Anyway, on our southern leg of the recordings, we booked into a fine hotel.

Any field trip will come with its light moments. I never quite mentioned this to anyone, but a couple of times I felt apprehensive on how far away the power generator was situated, especially in the Mwishoroni area near Mombasa. Someone could pinch the spluttering and roaring thing, I thought, and run off with it. By the time we realized that the resulting outage was not caused by the state-owned power supply company, the crook would be near Mombasa headed for a pawn shop.

And any field job with local respondents needs a “fixer”. We had one in one Deche. Interesting fellow. He made sure we got the groups we were seeking. But by late afternoon of each day, he didn’t seem quite sober to me. On our last night, he almost dragged me out of the hotel for a “final night out” – he was buying, he repeated over and over again. I have never been known to refuse an offer for good old Tusker. But I fled. Deche, don’t worry, I’ll buy you one – provided we both start at the same line!

By midway through the recordings, the teams were calling me “GPS”. I love gadgetry and had carried a simple dash-mounted locator. Even with its out-dated maps, we could find a place or two (with Steve doing the searches), but off-road, the device pleaded with us to tell it where on earth it was. So much for my pseudo-title of “Leader and Guide of the March 2011 Revolution”.

We covered over 1, 500 kilometers (some 980 miles) on Kenya’s narrow roads. I duly informed our partners that, once on a Kenyan “highway”, life expectancy drops by 25%. But Jimmy seemed to enjoy it all, counting how many “near misses” we encountered on the entire trip (luckily, he was in the Tabu-powered utility Land Cruiser while I crawled in its more sisterly version, the Prado, with the rest of the crew). Back in the capital Friday night, safely congregated around a table to munch tibs and zigni at an Amharic restaurant, I declared to us all that our life expectancy had sprung back to normal. Which is about 85% in these parts.

We came back to Nairobi with the total satisfaction that the trip was a success. However, we are still a long way from ultimate goal. We intend to use the period between now and mid-October to deliver our side of the deal. This shall be discussed and planned carefully and should take a concrete direction as we go along. We want to assemble a credible and convincing pilot that should alter the image of traditional music, especially by the media and policy makers – all who influence the larger population. Obviously, funding has always been a setback for projects such as this one. Yet we won’t sit back as bus passengers as our partners sink their energies into seeking funding for the Project. Ketebul Music has a major role to play here and we look forward to relishing along with Abubilla Music, not in the too distant future, the fruits of our efforts; Kenyan traditional music in attractive, easy to access media that shall keep it within the strides of today’s contemporary music. This is not a job, it’s a mission.

And, oh, we can’t wait to go west, deep into the Luo and Luhya land!

– Maddo,

April 10, 2011

Chairman, Ketebul Music

(also referred to in the banking industry as “Paul Kelemba”)